The Master of Black-on-Black: How Maria Martinez Transformed Pueblo Ceramics

Maria Martinez (c. 1887-1980) was an American artist who, with her husband, Julian Martinez, pioneered a pottery style comprising a black-on-black design with matte and glossy finishes. This revolutionary ceramic technique would not only transform the pottery traditions of San Ildefonso Pueblo but also elevate Native American ceramics to the level of fine art, earning international recognition and changing the economic landscape of Pueblo communities forever.

The Birth of an Innovation

María Poveka Montoya Martinez was from the San Ildefonso Pueblo, a community located 20 miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Born into the Tewa tribe around 1887, Maria learned pottery making through the traditional method of observation, watching other potters, namely her aunt, Nicholasa Peña Montoya. By the age of thirteen, she was already celebrated for her skill.

The breakthrough that would define her legacy came through collaboration with archaeologist Dr. Edgar Lee Hewett. Between 1907 and 1909, Hewett sought out skilled Pueblo potters who could re-create the ancient pots in biscuit ware. Working with pottery shards discovered during excavations of prehistoric Ancestral Pueblo sites, Maria and her husband Julian began experimenting with ancient techniques.

Sometime between 1918 and 1920 Maria Martinez and Julian Martinez invented an entirely new type of Pueblo pottery: black-on-black ware. This wasn’t simply a recreation of ancient techniques—it was an innovative adaptation that created something entirely new.

The Revolutionary Technique

The black-on-black pottery style that Maria Martinez developed was a complex process that required exceptional skill and precision. Taking a cue from Santa Clara pots, they discovered that smothering the fire with powdered manure removed the oxygen while retaining the heat and resulted in a pot that was blackened.

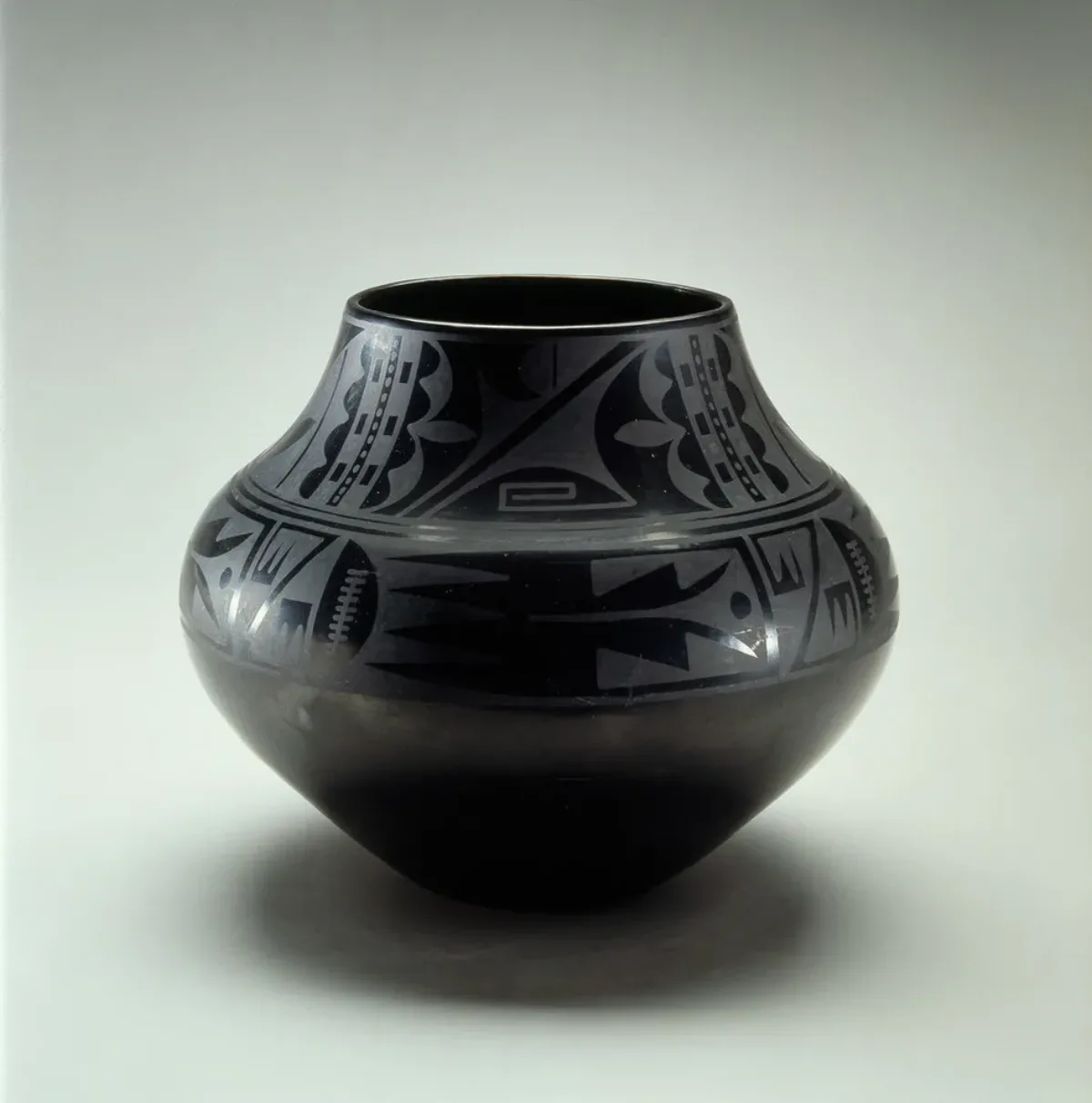

The distinctive appearance came from the contrast between different surface treatments on the same vessel. This unique process allowed matte designs to be painted on a stone-polished surface, a stone-polished piece fired black. The areas that were burnished had a shiny black surface and the areas painted with guaco were matte designs based on natural phenomena, such as rain clouds, bird feathers, rows of planted corn, and the flow of rivers.

The collaborative nature of the work was essential to its success. Maria’s forte was in construction of the ceramic vessel and stone polishing the outside slip. Julian Martinez a well-respected watercolor artist, was the painter of Maria’s early pottery. This partnership combined Maria’s exceptional technical skills in shaping and polishing with Julian’s artistic vision for surface decoration.

Technical Mastery and Innovation

Maria’s technical abilities were extraordinary. Maria’s expertise showed in her unique vessel shapes, which were of exceptional symmetry with walls of even thickness and surfaces free of imperfection. Her vessels were created using traditional hand-building techniques, carefully constructed from coils of clay mixed with volcanic ash found locally.

She experimented with the idea that an “unfired polished red vessel which was painted with a red slip on top of the polish and then fired in a smudging fire at a relatively cool temperature would result in a deep glossy black background with dull black decoration.” This careful manipulation of firing conditions and surface treatments created the distinctive visual effects that made her pottery so remarkable.

Cultural and Economic Impact

The success of Maria Martinez’s black-on-black pottery had profound effects beyond artistic achievement. At the time, this unique and distinctive style of pottery quickly became a success, and by 1922, it was made by nearly every potter at San Ildefonso Pueblo. It helped to change the economy of Pueblo as pottery became a successful career.

After perfecting the process, the pair taught the method to others, and by 1925 most San Ildefonso potters were making black-on-black ware. This generous sharing of knowledge demonstrated Maria’s commitment to her community’s wellbeing and economic prosperity.

The pottery also appealed to contemporary aesthetic sensibilities. The geometric designs and sleek finishes brought to mind the Art Deco style that was fashionable at the time, and their pieces were acquired by collectors and museums throughout the world. In part, the national popularity of their pottery can be attributed to the ease with which the smooth, geometric shapes matched the art deco style of design of the 1930s and 1940s.

Artistic Recognition and Legacy

Maria Martinez became one of the first Pueblo potters to sign her work, initially as “Marie,” later as “Marie & Julian,” and after Julian’s death in 1943, working with other family members. She was encouraged to sign her pots, becoming the first Pueblo potter to do so. They began to be regarded as works of art rather than household or ritual vessels.

Her achievements brought unprecedented recognition to Native American ceramics. Martinez was awarded two honorary doctorates, had her portrait made by the noted American sculptor Malvina Hoffman, and in 1978 was offered a major exhibition by the Smithsonian Institution’s Renwick Gallery. Her work is represented in major museums worldwide, and pieces have sold at auction for hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Continuing the Tradition

After Julian’s death in 1943, Maria continued working with family members, including her daughter-in-law Santana and later her son Popovi Da. In 1956, Maria started working with her son, Popovi Da. Maria made the pottery, and Popovi painted the designs. These are often considered among the best of her career after her early work with Julian.

The Martinez family legacy continues today through multiple generations of potters who maintain the traditions while adding their own innovations, ensuring that Maria’s revolutionary black-on-black pottery style remains a living tradition rather than merely a historical achievement.

Conclusion

Maria Martinez’s development of the black-on-black pottery style represents far more than a technical innovation in ceramics. It embodied a successful fusion of ancient traditions with contemporary aesthetics, created economic opportunities for an entire community, and elevated Native American pottery to international art status. Her work demonstrated that traditional Native American art forms could thrive in the modern world while maintaining their cultural integrity and significance.

Through her mastery of clay, fire, and surface treatment, Maria Martinez created a ceramic style that was both deeply rooted in Pueblo tradition and remarkably modern in its appeal. Her black-on-black pottery stands as a testament to the power of innovation within tradition, showing how ancient techniques could be reimagined to create something entirely new and profoundly beautiful.